contact us

contact us

2026/02/02

Fruit has long been valued as a widely accessible source of sweetness and nutrition across cultures and regions. History also shows how strongly people have pursued “freshness”: in the Tang Dynasty, imperial couriers traveled long distances to deliver fresh lychees to the palace; in southern China, an exiled official once joked about eating hundreds of lychees a day; and in France, Louis XIV built the Orangerie at Versailles so strawberries could be produced and enjoyed even in the winter. This long-standing demand for freshness is exactly what modern supply chains aim to deliver at scale.

Today, technologies such as cold-chain management, controlled-atmosphere storage, and faster global transport have made fresh produce available year-round and at wider scale. However, this convenience comes with a major operational challenge: post-harvest losses remain a weak point in the supply chain. Moisture loss, ethylene damage, and microbial growth steadily reduce quality, and in severe cases, produce spoils and must be discarded. Today, suppliers rely on proven technologies and standardized handling protocols. The objective is not only to move produce across borders, but to keep quality stable and predictable during weeks of sea transport by slowing physiological change and minimizing deterioration from harvest to arrival.

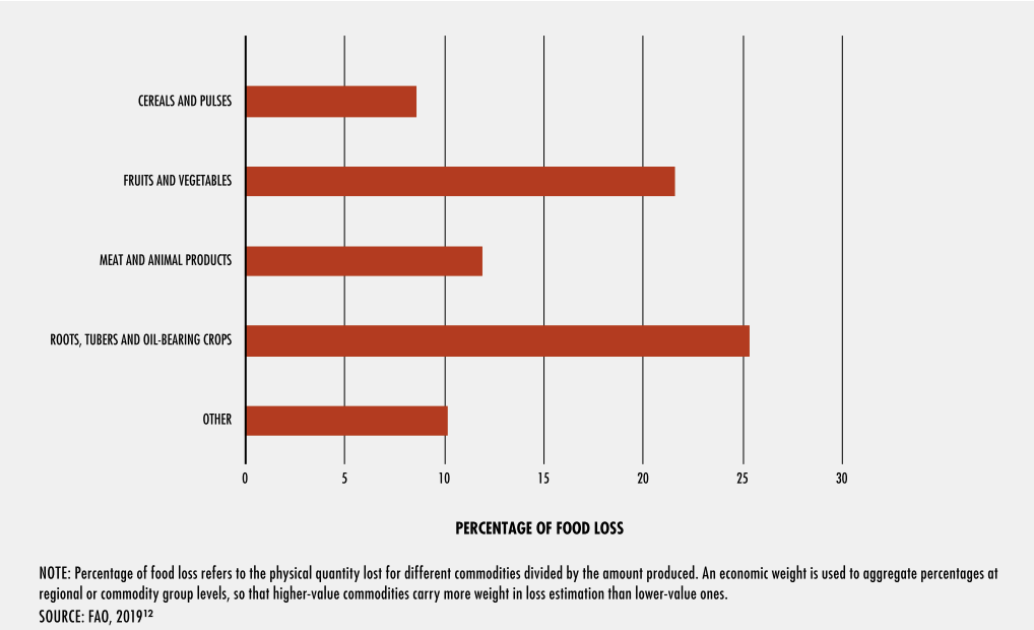

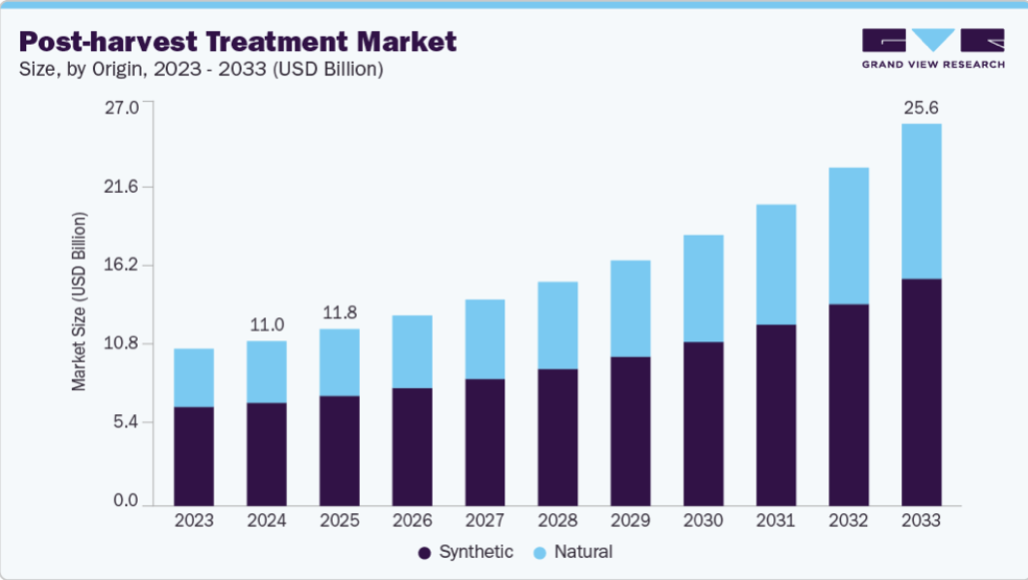

According to FAO’s The State of Food and Agriculture 2019, physical losses of fruits and vegetables during the “post-harvest to distribution” stage exceed 20%. This highlights post-harvest handling and logistics as among the most loss-intensive parts of the supply chain (Figure 1) [1]. Meanwhile, market analysis such as Grand View Research shows rapid growth in the global post-harvest treatment market, reflecting increased investment in solutions that reduce losses and improve quality consistency at arrival (Figure 2) [2].

For exporters, the value of these technologies extends beyond shelf-life extension. They transform what would otherwise become compost, landfill, or incineration losses back into saleable quality and more predictable revenue. Solutions such as AnsiP® and LytoFresh emphasize reproducible processes and scientifically defined control points, helping turn freshness preservation from a recurring cost into a strategic investment that improves export competitiveness and order reliability.

Figure 1.Percentage of food loss by commodity group at the post-harvest to distribution stage in 2016, based on FAO, The State of Food and Agriculture 2019.

Figure 2. Projected global post-harvest treatment market size and growth trends from 2023 to 2033, estimated by Grand View Research.

To maintain quality over weeks of maritime transport, the industry must first address the underlying mechanisms of deterioration. Four primary factors drive post-harvest quality decline and loss of marketability: respiration and transpiration, temperature fluctuations, ethylene-induced ripening, and microbial invasion.

Respiration and Transpiration:

Even after harvesting, fruits and vegetables remain as living tissues. Respiration consumes stored sugars and organic acids to sustain basic metabolism, while transpiration continuously drives water loss. Elevated respiration accelerates nutrient depletion and softening, and moisture loss leads to shriveling, reduced firmness, and lower saleable weight. In export markets where pricing is often weight-based and texture defines the grade, these physiological changes can translate directly into economic loss [3].

Temperature Fluctuations:

Temperature is the most critical variable governing post-harvest physiology. When cold-chain control is unstable, respiration rises sharply, accelerating energy depletion and quality decline. Temperature swings also increase the risk of condensation inside packaging, which raises surface moisture and creates favorable conditions for microbial growth. In addition, for chilling-sensitive crops, exposure to temperatures below critical thresholds can cause chilling injury and uneven ripening. While low temperatures slow metabolism, even brief lapses in control can rapidly amplify downstream losses [4].

Ethylene (C₂H₄)-Induced Ripening:

Ethylene is a naturally occurring plant hormone that can strongly accelerate ripening during long-distance shipping. In sealed or poorly ventilated systems, ethylene can accumulate, and even a small number of overripe fruits may trigger faster ripening and softening across the load. This can lead to rapid shifts in firmness, color change, and overall marketability, making ethylene management a central control point in freshness technologies [5].

Microbial Invasion:

After harvesting, produce has weakened defenses and becomes more vulnerable to pathogens. Over weeks of transport, fungi and bacteria can enter through microscopic wounds, stem ends, or natural openings. As tissues soften and free moisture increases, microbial growth and spread accelerate, leading to decay and off-flavor. Beyond direct disposal losses, these issues can also drive returns, claims, and longer-term brand damage in export channels [6].

Understanding these four threats leads to a clear conclusion: preserving freshness cannot depend on refrigeration alone. It requires a coordinated, end-to-end strategy across the supply chain.

LytoFresh is an integrated freshness preservation system designed to operate across multiple stages of production and export (Figure 3). Before harvesting, it supports crop nutrition and field management to improve plant resilience and reduce post-harvest susceptibility. During post-harvest handling, it focuses on the most common export failure points, especially microbial growth and ethylene-driven ripening, using antimicrobial, anti-mold, and ethylene-management approaches. Finally, by combining cold-chain logistics with standardized process control, the system keeps quality variation within predictable limits and improves arrival consistency. In practice, this reduces waste, downgrades, and claims while increasing the share of product that reaches higher saleable grades and supporting more reliable order fulfillment.

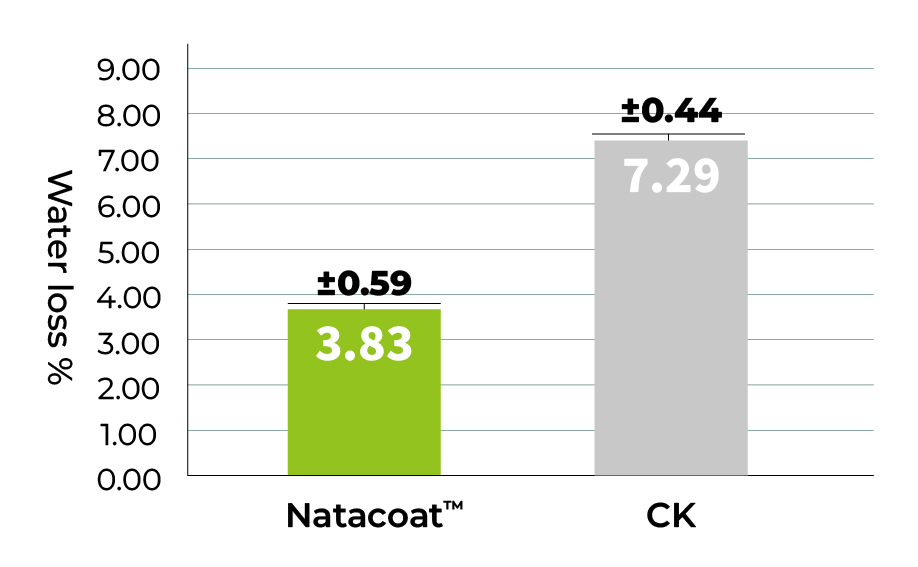

Studies suggest that wax coatings can slow key ripening processes in climacteric fruits (such as apples and pears) by reducing ethylene output and respiration. This helps delay softening, retain nutritional quality, and support antioxidant capacity, which together can extend shelf life [7]. Natacoat™ (part of the LytoFresh portfolio) uses wax emulsions to reduce moisture loss. Under simulated sea-freight conditions for Jin-Huang mangoes shipped to Canada, Natacoat™ reduced water loss and helped maintain overall fruit quality. As shown in Table 1, wax-treated fruit has about a 3% lower water-loss rate than untreated controls, and Figure 4 shows less peel shriveling consistent with reduced dehydration.

Table 1.Comparison of fruit weight loss rates under different storage temperatures, with and without wax coating.

Figure 4. Wax coating treatment effectively reduces water loss–induced shriveling.

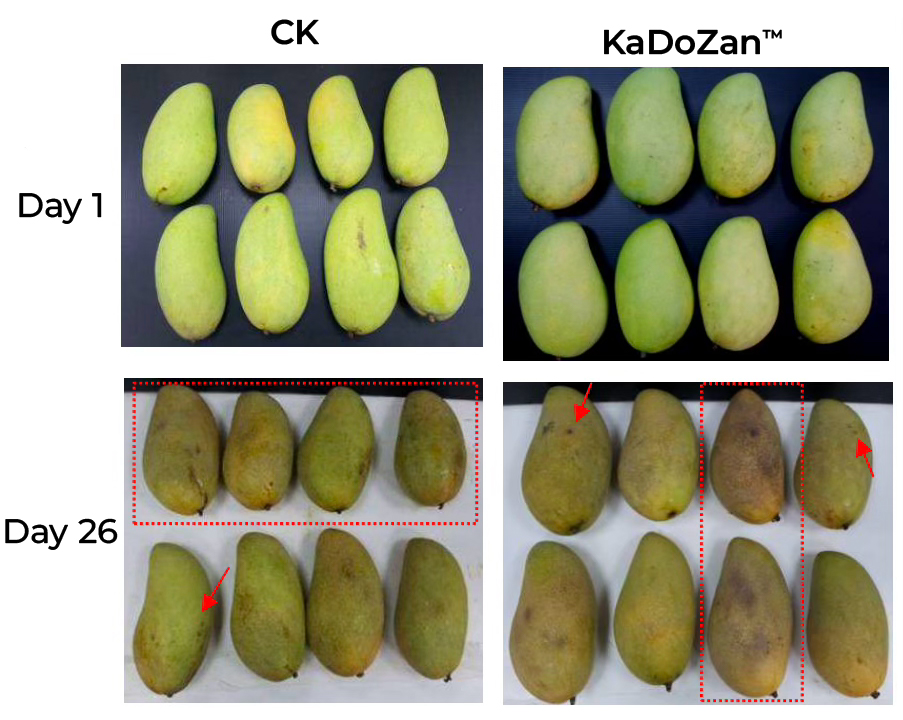

Chitosan can support post-harvest disease control through two complementary pathways: direct suppression of pathogens and stimulation of the fruit’s own defense responses. When applied to the fruit surface, it forms a thin semi-permeable film that can slow gas exchange, reduce respiration, and limit moisture loss, making it a relatively low-toxicity and environmentally friendly option compared with many conventional fungicides [8]. In simulated Canadian shipping conditions (10 °C, 26 days), the chitosan-based product KaDoZan™ reduced anthracnose incidence, with lesions observed on two fruits versus four fruits in the untreated control group.

Figure 5. Inhibitory effect of KaDoZan® treatment on fruit rot disease in Jin-Huang mangoes.

Figure 5. Inhibitory effect of KaDoZan® treatment on fruit rot disease in Jin-Huang mangoes.

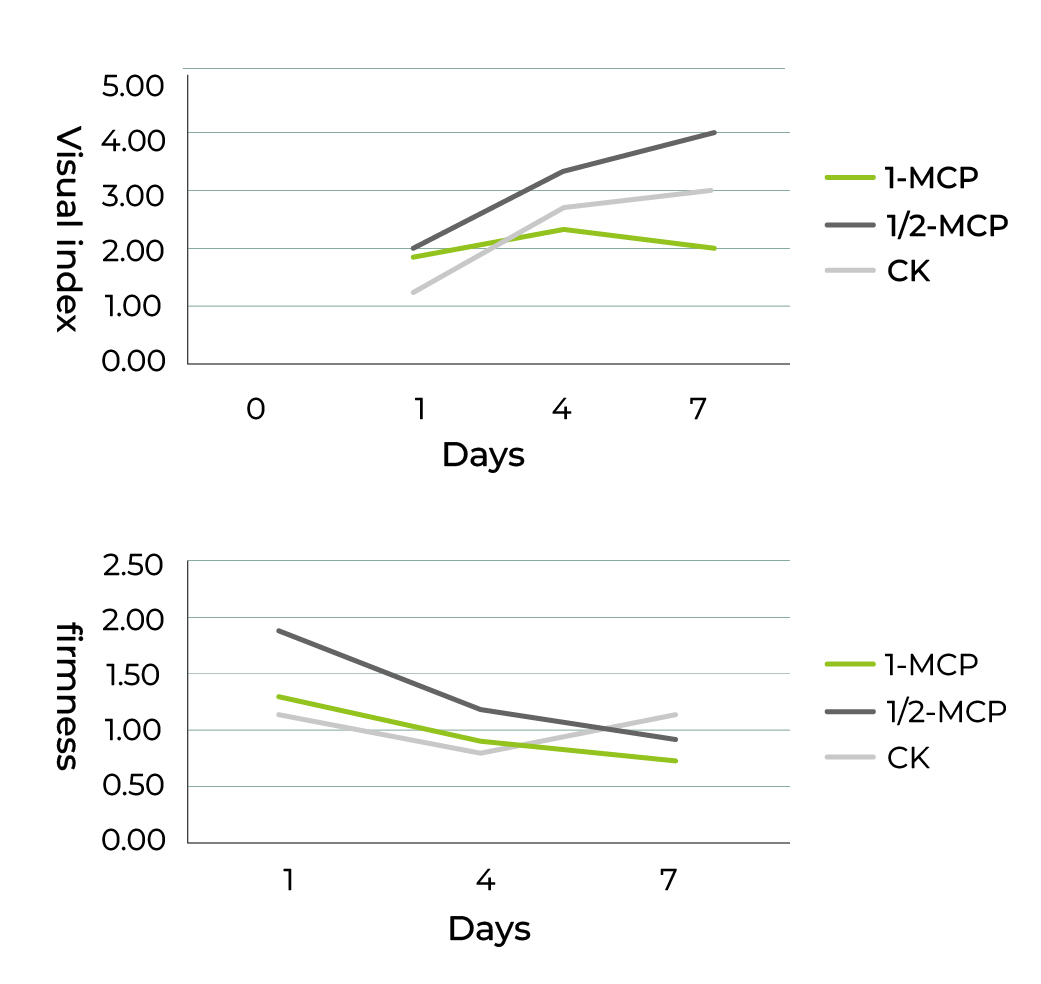

In addition, Ansip™-G and Ansip™-S are 1-methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) products that inhibit ethylene perception and slow fruit deterioration [9]. In storage trials with Kent mangoes, fruit treated with either full or half doses of 1-MCP and stored at 8 °C for four weeks maintained better visual quality and firmness after rewarming to 25 °C than untreated controls. (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Changes in appearance index (A) and firmness (B) of ripened Kent mangoes treated with 1-MCP (1 tablet Ansip™-G), ½ 1-MCP (½ tablet Ansip™-G), or CK (untreated control) after 4 weeks of storage at 8 °C.

FAO data indicate that physical losses of fruits and vegetables during the “post-harvest to distribution” stage can reach 21.6%, meaning a substantial share of production is lost before it ever reaches consumers. This “invisible black hole” erodes profits for growers and exporters alike and points to a practical reality: one of the most effective leverage points for reducing food loss is post-harvest preservation.

Once produce leaves the field, quality declines through several predictable pathways. Water loss driven mainly by transpiration reduces weight and firmness. Breaks in cold-chain control accelerate metabolism and raise condensation risk. Ethylene can speed ripening and softening, while microbes exploit wounds and surface moisture to initiate decay. Refrigeration remains essential, but temperature control alone is often not enough to keep quality stable over weeks of transport. The LytoFresh system aims to shift freshness preservation from experience-based handling to science-driven control by integrating field nutrition, targeted inputs, and microbial management into a reproducible protection framework.

Experimental results illustrate how this works in practice. Natacoat™ reduced moisture loss in Jin-Huang mangoes by about 3% and mitigated shriveling. KaDoZan™ lowered disease incidence and improved arrival appearance. The Ansip™ series suppressed ethylene signaling, delayed softening, and maintained appearance indices. With an integrated approach, export freshness becomes more than an added expense; it functions as a strategic investment that reduces waste, downgrades, and returns while supporting more stable product value and stronger international competitiveness.

Consumer questions often focus on safety, whether washing is needed, and potential impacts on flavor or nutrition. Post-harvest treatments used in supply chains are typically managed under food safety regulations and industry standards, and their use and verification depend on the crop and application context. Because methods and compliance requirements vary widely, these topics will be addressed in the next article from a more consumer-oriented perspective.

1. Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; FAO, Ed.; The state of food and agriculture; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, 2019; ISBN 978-92-5-131789-1.

2. Post-Harvest Treatment Market Size | Industry Report, 2033 Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/post-harvest-treatment-market-report (accessed on 22 January 2026).

3. GALINDO, F.G.; HERPPICH, W.; GEKAS, V.; SJÖHOLM, I. Factors Affecting Quality and Postharvest Properties of Vegetables: Integration of Water Relations and Metabolism. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2004, 44, 139–154, doi:10.1080/10408690490424649.

4. Badia-Melis, R.; Mc Carthy, U.; Ruiz-Garcia, L.; Garcia-Hierro, J.; Robla Villalba, J.I. New Trends in Cold Chain Monitoring Applications - A Review. Food Control 2018, 86, 170–182, doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.11.022.

5. Cocetta, G.; Natalini, A. Ethylene: Management and Breeding for Postharvest Quality in Vegetable Crops. A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.968315.

6. Zhao, P.; Ndayambaje, J.P.; Liu, X.; Xia, X. Microbial Spoilage of Fruits: A Review on Causes and Prevention Methods. Food Reviews International 2022, 38, 225–246, doi:10.1080/87559129.2020.1858859.

7. Si, Y.; Liu, J.; Ji, Y.; Li, C.; Li, H.; Nie, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, A.; Yuan, H. Postharvest Wax Coating Treatment Extends Shelf Life of Climacteric Fruits by Delaying Ripening, Improving Storage Quality and Antioxidant Potential. Food Qual Saf 2025, fyaf064, doi:10.1093/fqsafe/fyaf064.

8. Romanazzi, G.; Feliziani, E.; Baños, S.B.; Sivakumar, D. Shelf Life Extension of Fresh Fruit and Vegetables by Chitosan Treatment. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2017, 57, 579–601, doi:10.1080/10408398.2014.900474.

9. Watkins, C.B. The Use of 1-Methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) on Fruits and Vegetables. Biotechnol Adv 2006, 24, 389–409, doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2006.01.005.